Our Story

A place of ideas and inspiration

Life, food and art have long been integral to 86 River Road, Emu Plains. For more than seven decades the garden and home have echoed with the sound of parties, lively debate and creative passion and today – as Penrith Regional Gallery, home of The Lewers Bequest – it provides a vibrant program of exhibitions and activities and a place for visitors to discover, share and enjoy.

The site was once a small rural holding on the banks of the Nepean River, and part of the early settlement of the Nepean district. The original house, now known as Lewers House, was built in 1905 and in 1942, Margo and Gerald Lewers – two leading artists in the development of modernism in Australian art – bought the property and made it their home and studio. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s it was known as a place of style, innovation and hospitality. As Patrick White wrote:

“ideas hurtled, argument flared, voices shouted, sparks flew … It was a place in which people gathered spontaneously.”

The isolation of the house enabled Gerald to work on his sculptures – especially the larger carved stone pieces – without fear of disturbing the neighbours. The placement of Gerald’s sculptures within the garden is a subtle but significant design element, and something that visitors can enjoy today, along with examples of Margo’s work; including paintings, mosaic tiles, and Corkwall, a significant piece of Modernist design comprising a cupboard and display unit that can be seen in Ancher House.

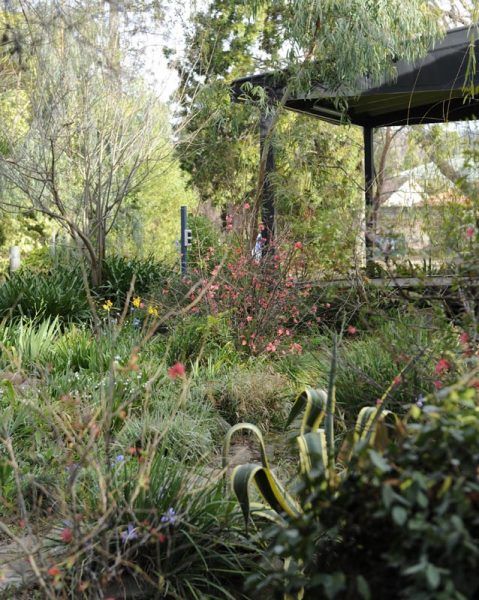

The garden played a pivotal role in the creative and artistic life of Margo and Gerald Lewers, in family life, and in entertaining family and friends – especially people also involved or interested in modern art and design. Today it is maintained by a Heritage Gardener in keeping with Margo’s original intent that it be a living work of art.

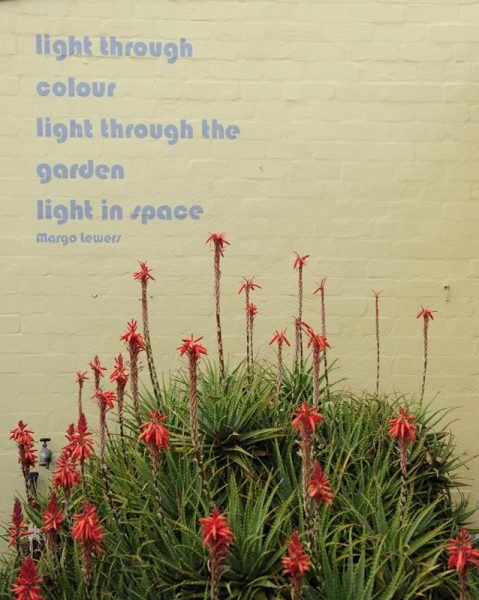

In 1956 architect Sydney Ancher remodelled elements of Lewers House to create a Modernist living room (today known as the Lounge Room Gallery), opening onto a new courtyard space with brick wall and nearby succulent garden. Ancher went on to design a second house on the site, known as Ancher House. This is the only example of Ancher’s work in Western Sydney and was a true collaboration between artist and architect. Interior decoration and detailing, including extensive mosaic work, was completed by Margo.

Following Gerald’s death in 1962, Margo continued to live and work at Emu Plains until she died in 1978. In 1980 the Lewers daughters, Darani and Tanya, donated the site, buildings and gardens to Penrith City Council, together with a substantial collection of art including works by Gerald and Margo and their contemporaries. Their vision was to create a centre of excellence for the presentation and appreciation of art for the community.

A creative life

The Garden

The garden played an integral role in the creative and artistic life of Margo and Gerald Lewers, in family life, and in entertaining family and friends – especially people also involved or interested in modern art and design.

Margo Lewers engaged family and friends, including architecture student friends of Tanya, and local friends and tenants to help with the maintenance of the garden and to undertake works that required considerable heft and strength, such as in the construction of the masonry wall retaining the Ancher House front garden.

Life with the Lewers

In the words of Gina Plate; the daughter of Margo’s brother, artist Carl Plate. She and sister Cassi were frequent visitors to the Lewers’ home.

“In all works at the property the Lewers family has as a conscious intention to integrate the buildings closely with the garden; and family activities and parties were always organised with the use and appreciation of the garden as an integral part of the event.

Margo loved bringing friends from different areas of the arts community together. She loved to have parties, which she organised whenever she felt inspired, (several times a year was the norm) or to welcome a troupe of actors say, such as the Shakespearean Company when they were touring the country. She held several themed fancy dress parties, sometimes to celebrate the New Year, but on other occasions as well- such as the marine party to which Tanya and Darani’s university friends were invited. And her dinners and weekend lunches (for 6 to 10 or 12 people) were frequent occurrences throughout the year.

Visitors arriving for a party were handed a ‘gin and two’ as they walked through the door- the ‘two’ being vermouths (sweet and dry) plus freshly squeezed orange and grapefruit juice made from fruit picked that afternoon from the citrus orchard which grew along the southern side of the property. These drinks quickly put everyone in party mode, but in fact the trip to the orchard with buckets to pick the fruit was a fun part of the preparations for those helping out on the day and put them in the mood from early afternoon. Similarly it was always a pleasure to be sent to the vegetable garden to collect salad and vegetables for what we knew would be another delicious meal: the luscious vegetables growing in the well-tended vegetable plot had an order about their arrangement in formal rows not experienced in the rest of the garden where a profusion of plants and colours were encouraged to spill out of their beds and onto pathways and surrounding areas of lawn. The neat formality of the vegetable garden still had a ‘Margo’ feel however, as the rows of vegetable and salad plants were interspersed with flowering annuals and flowering herbs which Margo would pick and strew over her salads with stunning visual effect. Edible flowering plants particularly favoured were violas, violets, nasturtium, calendula, marigold, heart’s –ease, bergamot, borage and chives which all looked pretty peeping out between the vegetable and salad plants and pretty when scattered over the beautifully arranged platters of food- bright blue borage flowers on the orange of a grated carrot salad, rusty red nasturtiums and ripe yellow calendula on green salad and subtle purple-pink of chive flowers and snipped green chive leaves over a potato salad for example.

Margo constantly nurtured the deep rich alluvial soil of the riverside property, digging in her own compost or ‘mulch’ as she called it, and adding plenty of manure. One of the pleasurable chores was to take the full bucket of kitchen scraps to empty into the mulch pit. As the pit was located well away from the kitchen under the bottle tree towards the front fence, a trip to the pit entailed a wander through the garden past the vegetable garden where its order and fecundity could be experienced and back through other parts of the garden where the latest plants in flower could be admired, sniffed or picked. If it was near dusk, the bamboo clump nearby would be alive with chatter and rustle of what seemed like thousands of birds settling down for the night.

From the earliest days, the garden was used as a gathering place for friends and family. The sloping wall was built in the 1950s to protect the garden at the back of the house from the heat and dust generated by westerly winds blowing across the then, un-built on farmland at the base of the Blue Mountains. This wall created a pleasant courtyard, which was shaded by the lacy leaves of the Jacaranda, one of the few trees on the site when purchased by Gerald and Margo. When the weather was fine and sunny and not too hot, lunch was carried out on large woven (rice winnowing?) trays and eaten at the mosaic-topped table made by Margo in the shade of the Jacaranda, and discussions and lively debate could detain the participants there all afternoon, with the children lounging on the swing seat nearby, half listening dreamily to the conversation, or running off to play and explore the garden after the meal. The courtyard garden was mad enticing during night-time parties when hand-painted or clear fairy lights (made with ordinary light globes) were strung through the Jacaranda. This was in the days before commercially bought fairy lights festooned the front yard and façade of every house in the suburbs, so the effect of the lights was more enchanting and novel than they might be today.

During their childhood, Darani and Tanya had a net, which would be strung up, across the courtyard and they would play a volley-ball like game with a rope ring. When they were teenagers and had school friends stay, or later, when they had groups of University friends for a weekend, Gerry would make a fire on a piece of corrugated iron in the middle of the courtyard around which they would sit to eat their dinner and spend the evening talking. Darani’s August marriage was also celebrated in this way, with guests warming themselves during the night-time celebrations around a fire on corrugated iron.

On hot summer’s days the timber verandah at the front of the house was where lunch was eaten or afternoon tea taken. From this shady elevated platform, the front garden, highlighted in the sun, could be enjoyed in the foreground, with glimpses of the Nepean River glistening through the garden and riverbank-trees in the background. The watery sound of frogs ‘glop glopping’ in the pond below the verandah edge, the tender green strands of the weeping willow trailing down and the extended canvas verandah blinds all helped create an impression of coolness.

This verandah was also the perfect spot to gather and watch the Easter egg hunt. Trays and baskets filled with brightly wrapped Easter eggs nestled in coloured cellophane ‘straw’ were brought around and the eggs were hidden in the garden to be discovered by the delighted children watched over by the adults sitting on the shaded verandah.

This was the verandah where the painter Desiderius Orban held his summer school painting classes in the 1940’s for small groups of interested family members and friends. Still life’s were set up in the relative cool of the verandah, though the painters would also sit out in the garden, still in its more primitive, undeveloped form, and the broader landscape around the house were also the subject of many water colours and drawings. Participants slept on beds on the concrete verandah.

A wide, smooth concrete verandah surrounds most of the original house, linking it with the timber verandahs, the bathroom and the renovated kitchen and living room wing. Nowhere is it more than 3 or 4 steps down to the garden. The renovations for the new wing included a stone flagged verandah as a transition space between the living room and the garden, echoing the function of the other verandahs. As it had a rough and uneven surface, this verandah was never used as a dining area but during parties, to which 20 to 50 people were usually invited, guests spilled out of the living room on to the stone verandah and from thence, onto the courtyard lawn and into the garden.

The concrete verandah was not only a covered pathway between the buildings and the garden, it was also another place to rest and chat within the view of the garden. Margo had several steel-grey vinyl-covered day beds scattered around the verandah which were moved about depending on the time of day, or the season, either to catch the sun (in winter) or to be in shade (in summer). Here people would sit and chat in comfort. At night, ‘left-over’ party guests slept out on these beds, protected from mosquitoes under coloured mosquito nets hand-dyed bright colours by Margo (pink, yellow, green, blue and red). During the day, the nets, tied up in colourful hanging knots were glimpsed through the vegetation as one walked about the garden. In the morning it was a treat to awaken to bird song, with sunlight warming your face and for a bit of the garden to be first thing you’d see on opening your eyes.

The rhythm of any day, particularly in summer, revolved around the systematic watering of the garden. A trip often had to be made down the track, under River Road, to prime the pump which brought water up from the Nepean River to fill the tank elevated on a vine covered stand high above the garden. Then, throughout the day numerous trips were made to move the watering system about the beds to ensure complete coverage, and the air was filled with the swish-swish-swish of the fixed irrigators flicking out water. Darani remembers that as children they were always put to work watering whatever vegetables were being grown on a large scale- pumpkins or asparagus for example, or requested to collect fallen pecans or walnuts as a pre-condition for being allowed to go for a swim in the river.

Margo’s flower arrangements were inspiring ensembles of flowers grown in the garden, picked first thing in the morning, stored in a deep bucket of water in the cool pantry off the kitchen and arranged shortly before the arrival of guests. Rather than having a separate ‘picking garden’ which would have been possible given the amount of space, Margo integrated the flowers and plants she liked to use in her arrangements in the general planting design of the whole garden. She was also very generous in her gifts of flowers to friends she visited- usually taking a big bucket of flowers picked in the morning if she was invited to lunch or dinner or away for the weekend.

The garden, created by Margo and Gerry Lewers was regarded by them as a living work of art to be experienced and enjoyed by family, friends and other visitors from within the house, from the verandahs and within the garden itself. Paintings and acrylic constructions hanging on a wall, mosaic tiled floor designs and carved sculptures and copper downpipes are essentially static works of art; the garden was an ever-changing, living, ‘breathing’ work-in-progress. An extension of Margo and Gerry’s creative Oeuvre, the garden was constantly tended and nurtured, and everyone was encouraged to share its pleasures and surprises.”

Photos: Adam Hollingworth

Words: Gina Plate